Electricity Bare Basics

When you dive into the realm of appliances, you’re going to be dealing with electricity and the various components associated with them. In this module, we’re going to breeze over the bare basics that you need to know to fully grasp and comprehend how electricity works in the application in which you’re working on.

Electric Load

Throughout this course, you’re going to get familiar with the term “load.” An electrical load is anything that consumes electrical energy and converts it into something we can use, like light or heat.

- A drain pump is a load. It uses electrical energy to spin an impeller, which then expels water from a unit.

- A heating element is a load. It takes two 120 VAC lines that are out of phase with one another, and generates heat through the resistive element. (More on that later.)

Conductor

When it comes to supplying voltage to a load, we need a means to do that. These are called conductors – most commonly, “wires.” A conductor is simply a material or substance that allows electricity to flow through it. Certain materials have more conductivity than others.

- A piece of wood, for instance, has next to no electrical conductivity. You can place a live 120 VAC line to it, and touch any other point on the piece of wood and not have to worry about getting shocked (unless the piece of wood is soaking wet).

- A length of copper, on the other hand, is very conductive.

When it comes down to conductivity we want the least amount resistance from Point A to Point B. (Don’t worry, we’re going to dive into this much deeper in a bit). When we introduce resistance into a circuit, we loose voltage at that resistance. That resistance steals some of the voltage from where we want it. Copper and Silver are among the best conductors because they accommodate electron flow with very little resistance.

Comparison – Conductor vs. Load

An electric load is any device or component that consumes electrical power to perform work, convert energy, or produce heat. The key requirements that differentiate a load from a simple conductor include:

Resistance (or Impedance):

-

A load must oppose the flow of electrical current in some way, typically through resistance (Ω).

-

A pure conductor, like a wire, has very low resistance and is not considered a load unless it carries excessive current and starts dissipating power as heat (which is usually unintended).

Power Consumption:

-

A load converts electrical energy into another form, such as:

-

Mechanical energy (e.g., motors)

-

Thermal energy (e.g., heating elements)

-

Light (e.g., LEDs, incandescent bulbs)

-

Sound (e.g., speakers)

-

-

A conductor does not significantly consume energy but instead facilitates its transfer.

Voltage Drop:

-

A load must create a voltage drop when current flows through it. (More on this later – it’s an extremely important concept to understand.)

-

In an ideal conductor, the voltage drop is negligible, whereas a load has a measurable drop due to its resistance or impedance.

Work Output or Energy Conversion:

-

A load performs useful work or converts electricity into another usable form.

-

A conductor simply transports electricity without altering its primary form.

Other Terms

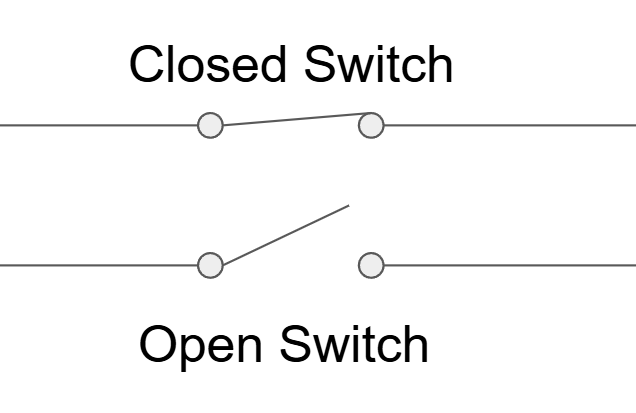

Switch

Simply put, a switch is a conductor that opens and closes a circuit. A switch is not a load. It does not produce an output. It only works to open and close a circuit. Therefore, a switch, when closed, should have very low resistance. If we were to have, say, a loose connection or a damaged contact inside the switch that creates additional resistance, it is going to generate heat as the electrons try to push through it.

- When the switch is “closed,” this means it is shut, and making contact.

- When the switch is “open,” this means it is open, and the circuit is open.

Short

An electrical short occurs when electricity takes an unintended low-resistance path, bypassing the normal circuit. This usually happens when two points in a circuit that should have resistance between them are directly connected, allowing excessive current to flow. This can lead to overheating, damage to components, or even fire if not properly controlled. Shorts are often caused by damaged insulation, faulty wiring, or accidental contact between conductors.

While we’ll get into it deeper later, when line and neutral are connected to a load, the resistance of that load, or in that circuit, restricts current flow.

If line and neutral were connected directly to one another, then there is nothing to restrict current flow other than the resistance of the wire. Electrons would rocket to near infinity, until a failure occurs – such as the breaker tripping or the wires melting and opening the circuit.

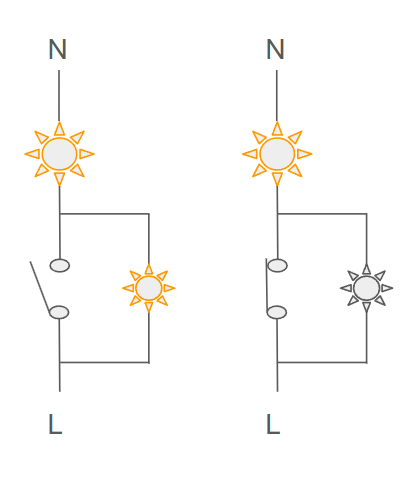

Shunt

You really don’t see these too often in appliances, but they are there, most commonly in gas dryer heating circuits.

A shunt is an electrical bypass. It is in essence a switch that when closed, circumvents a load.

The key thing with shunts is that they need to be placed in a circuit such that, when closed, it does not cause an electrical short.

Another key concept to understand about electricity is that electrons follow the path of least resistance.

Left Diagram

In the diagram to the left, the switch is open. That switch is a shunt that is open. Voltage is then forced through both lightbulbs, and both will illuminate. Since it’s a series circuit, voltage will be dropped proportionality across each bulb (more on voltage drop later).

Right Diagram

In the right diagram, the switch is closed. Electricity then follows the path of least resistance, and viola, the light in the secondary circuit no longer illuminates. Only the other one does.

In the dryer module, we go over this application in more detail.

Electrical Terms

Resistance

Resistance (Ω) is the measure of how much a material or component opposes the flow of electric current.

- Higher resistance = less current.

- Lower resistance = more current.

Think of it like this: The more a load resists, the less current you get. The less it resists, the more current you get.

Current is like a puppy in that it will take as much as it can get if you give it no resistance. If I were to let my dog have free reign over his food, the 50lb bag of food would be gone in 20 minutes. When I give him 2 scoops, I am restricting the flow of dog food.

Current

Current is the flow of electric charge through a conductor, measured in amperes (A). These are the electrons. Current, or amps, represents how much charge moves past a point in a circuit per second.

Current is not present in an open circuit. When the switch is open, and the circuit is open, there is no current. Current presents itself when the circuit is closed, and current is what makes the load do work.

Power/Watts

Power (Watts, W) is the rate at which electrical energy is used or converted into another form, such as heat, light, or motion.

**Difference Between Power and Current

The key difference between power (watts, W) and current (amperes, A) is:

-

Current (A) is the flow of electric charge through a circuit. It tells you how much electricity is moving but not how much work is being done.

-

Power (W) is the rate of energy conversion or how much work is being done by the electricity, such as producing heat, light, or motion.

Voltage

AC Voltage vs. DC Voltage

DC Voltage (Direct Current)

-

Definition: Voltage that remains constant and flows in one direction.

-

Source Examples: Batteries, solar panels, DC power supplies.

-

Usage: Common in low-voltage electronics, car batteries, and small devices.

AC Voltage (Alternating Current)

-

Definition: Voltage that changes direction periodically (typically in a sine wave pattern).

-

Source Examples: Household power outlets, generators, power grids.

-

Usage: Used for power transmission because it can be easily transformed to different voltages for efficiency.

Summary

We went over a lot of key concepts here, but they are the foundation to a comprehensive understanding of how electricity works. When you understand how electricity works, you will understand what your meter is telling you.