Wiring

In the dryer module, we dive into the breaker box and how it supplies L1 and L2 to the receptacles. What we’re going to look at here is an issue you will occasionally come across regarding the wiring at either the breaker or at the outlet.

Keep this in mind: Unless you’re a licensed electrician, you typically won’t be working on wiring issues behind the receptacle. However, it’s still important to understand potential failures on the “house side” that can impact the appliance’s performance.

Dropping Voltage Under Load

When you put your meter leads from L1 to L2 at the outlet, and you read 240 VAC, and you see 120 VAC on each Line to Ground or Neutral, this does not always indicate that the circuit is good. A loose connection or a spliced wire can still have enough conductivity for voltage to be present, but might fail when the electrons come surging through.

A common failure state that might point you toward voltage dropping under load is when you go to press Start, the unit seems to go dead, then will power back up. No matter how many times you try to start it, it will power off when a high voltage load is trying to activate.

Let’s look at why:

Electrons are the umph that get a load to kick to life and start running. They are the atomic particles that constitute amps, or current. The more electrons that pass a given point, the higher the current draw.

Electrons are powerful little particles. They generate heat when in motion. When a load is expected to have a higher current draw, a larger conductor is needed. This is why a standard lamp will have a relatively thin power cord, whereas an electric oven will have a much thicker cord. This is to afford the electrons the conductivity that they need to do what we want them to do, without melting the wire.

The thing to understand about electrons is that they do not travel within a conductor. They actually blast along the outside of a conductor. Hence the reason you’ve got some pretty robust insulation on the outside.

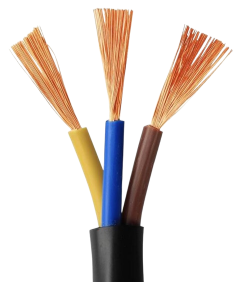

While we’re not going to dive into the difference between a solid core wire and a standard wire (standard wires are like the picture – lots of smaller copper wires – lots of surface area for them electrons), what you need to know is the surface area plays an important role.

Now, knowing how electrons travel along a conductor, we know that the conductor needs to be pretty solid. No loose connections, no breaks. When the electrons go blasting through, they get to where they need to be! When they have to jump a gap, guess what? They generate heat.

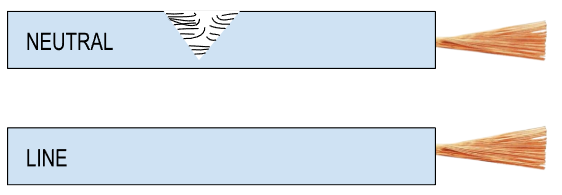

Now, look at the drawing of the Line and Neutral wire. Notice on the Neutral wire how a majority of the copper strands inside the insulator are broken? Maybe the wire brushed up against a piece of metal, or maybe someone tried to mount a TV and put a screw through half the wire.

At the bottom of the break in the Neutral wire, you can see there are some copper strands remaining intact. Voltage itself does not generate heat. It really does nothing other than sit there until the circuit is closed. So, you will read 120 VAC when you check from Line to Neutral on those wires when nothing in the circuit is doing any work.

But, when the circuit closes, and the electrons come blasting through, that break in the wire, or the loose connection all of a sudden have a lot of force on them. It can not start the unit. It fails under load.

Testing Voltage Dropping Under Load

So, how do you test for voltage dropping under load? It’s really quite simple.

You find where line and neutral connect to the timer or the control board. You put your leads there for AC voltage. You see 120 VAC. You try to start a cycle. If the voltage goes from 120 VAC down to, say, 8 VAC, the unit goes dead, then you see 120 VAC, then you know you’re dropping voltage under load and you’ve got an issue somewhere.

Summary

We went over a brief aspect to electricity in this module, but an important one. I can’t tell you how many tech’s I see improperly diagnose an outlet, and start throwing parts at the machine when none are needed.

I even had an instance where I found that the voltage to a dryer was dropping under load. I found this by checking L1 to L2 at the terminal block and trying to start a cycle. The voltage went from 240 VAC down to around 86 VAC, then returned to 240 VAC when the dryer gave up. I advised the customer that they needed an electrician, and left. A few days later, they reached back out to me and said an electrician came by and found nothing wrong with the circuit. Suffice it to say, they had a tone in their voice that I didn’t appreciate. I returned, made the same check, and found the same voltage readings. I cut the breaker, pulled the receptacle out and found a burnt wire at the connection.

I showed that to the customer, explained what was happening, advised them that they might want to hire a better electrician, and left.

Point of that story is, I have come in behind other techs, electricians, duct cleaners – you name it, “professionals” in their respective fields – just to find they did not do their job right. I am not a licensed electrician, nor do I know as much about electricity as I’d like, but I know the relevant aspects to do my job right.

Take this story as a strong advisory: Make your own checks. Use your own tried and true methods. They will not let you down. DO NOT assume because the last tech replaced a part, that it was the right part, or since an electrician was out, the house voltage is good. Prove it before you dismiss it.

Do not assume because they hired someone else to do something, that that person did it right. I’ve been out to countless calls where a dryer is taking too long to dry clothes. It’s heating, and their ducts were recently cleaned. I conducted some tests and found that there was an airflow restriction. I’ve had enough of these calls, in fact, where I bought a 50 foot endoscope that I would send all the way through the ducts. And I would record that process, and I would show them the video where that camera came up to a big ole’ wad of lint buildup.

As you can probably tell by now, I don’t like it when a customer thinks I don’t know what I am doing; I don’t like it when I start to think I don’t know what I am doing.

The purpose of most of the material you’ll see throughout this course is designed to teach you what you need to know to do your job right. I detail instances that have tripped me up in the past and my learning experiences from them.